Veda

2019

NECKLACE (Found sheep bones, found ceramic fragment, reclaimed lapislazuli bead, reclaimed copper wire)

Veda (Sanskrit: विद्या) is mainly translated as learning, philosophy, scholarship and knowledge, uniting together concepts not only of intellectual knowledge per se but a process of enquiry, reasoning and understanding, as per its etymological root Vid (Sanskrit: विद्), also shared in the verb to see (Latin videre), meaning “to reason upon, to find, to know, to understand”.

This piece was many years in the making and it is one of the best representations of the journey of “wisdom as practice” that I wish to take with my work.

One day several years ago, while at West Dean College, I took yet another stroll through the arboretum in search of the tomb of its founder, Edward James. This had so far eluded me and I could never understand how I could repeatedly miss a funerary monument. And when I finally stumbled upon it, it was nothing like what I had expected. I nearly walked over the stone slab, well tended to, but totally level with the grass covering in between the trees. And there was the first realisation that, by following my assumptions about what a grand tomb should look like, I had always been looking for the wrong thing. And therefore I had never found it… My eureka moment was instantly rewarded by finding, embedded in the ground barely inches away, two very beautiful ceramic fragments from the same plate. A gift for having gained one more grain of knowledge about myself and the world around me, I took them home and treasured them, waiting for the right moment to use them.

A couple of years after, on another visit to West Dean and another walk around the fields, I happened upon a large scatter of perfectly clean animal bones. The more I looked, the more there were. Was this a sheep that had been killed by a predator? Or a lamb that had died of natural causes? But the bones were too pristine… The archaeologist in me continued to build scenarios, while I quickly untied a light jumper from round my waist to fashion a carrying device to collect the lot. Lamenting the loss of life but mindful of the laws of nature, I was grateful for the bounty of practically an entire body, including still articulated legs, although I duly noted that unfortunately the head was missing. These I also took home and boxed them carefully, treasuring them waiting for the right moment to use them.

Since the beginning of working with narrative, even before I understood the significance of why I used or needed narrative itself as either material or process, I was very aware of my inability to tell a story that was not ready in my head. What I could not see in those early days was that, even if the story was there, it was my lack of understanding of it and of how it fitted in the grand scheme of the (or just my) cosmos that prevented me from putting the puzzle together. And this was the case with these ceramic fragments and treasure trove of bones. The only solution I could see was to take them back where they came from and acknowledge their provenance by working on them back at West Dean.

Once there, I was filled with grandiose ambitions to create a rather monumental neckpiece that would incorporate several of the larger leg bones and both the ceramic fragments. But no matter how much I strived, the piece was not coming together. The more I rearranged it, the more it felt like too much. And the more I was being intensely drawn to just one bone.

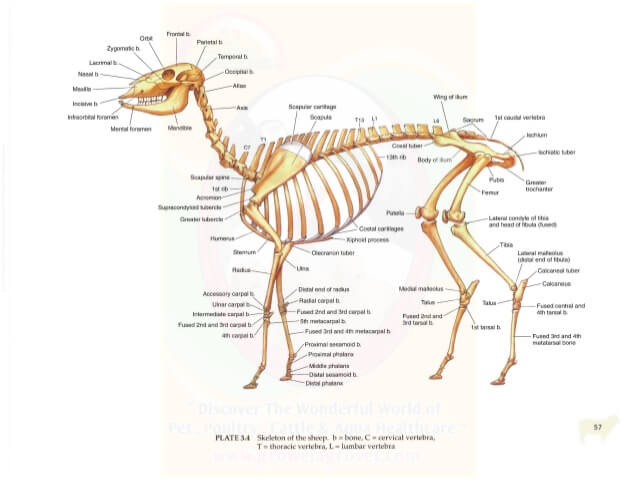

Having a modicum of understanding of skeletal anatomy, I could see this was a tail bone. Still, I took some time to research sheep anatomy.

(photo from Poultry & Farm Animals Anatomy by Growel Agrovet Private Ltd., available on Slideshare, slide 74/177)

This revealed that, of course, this was in fact none other than the sacrum bone, a name by which it is also known in Italian, and one I had known since biology classes at school and by hearing old ladies complain of lower back pain. And yet it had never occurred to me to research why it is called the the sacred bone, the holy bone. Delving deeper, I came to realise that this is in fact a name, or at least a connotation, that this particular bone shares across the world and from ancient times, mostly because of its role in aiding child bearing and birth. Its significance as a door to life was so strong that, in shamanistic cultures, it was considered a portal to another dimension.

The pieces of the puzzle where finally all there. I had learnt that I could only find when I could let go of my assumptions as to what I was looking for. And I was offered the final answer when I stopped committing hubris and instead allowed myself to feel what was calling me. As a final reward, I found in the box of objects I had brought with me one last reclaimed lapislazuli bead from a previous project, when in fact I had not remembered packing it nor in fact did I think I had any left. The lapis itself was considered, because of its deep blue appearance and golden specks, a symbol of the cosmos and the stone of truth.

We see when we are ready to open our eyes. And we find when we are ready to seek. And it is as a reminder of the journey of enquiry, reasoning and understanding that I went through with this piece, that it has come to be called “Veda”.